The following excerpt is from the upcoming book Kid Gavilan: The Cuban Hawk by F. Daniel Somrack.

Kid Gavilan – The Cuban Hawk

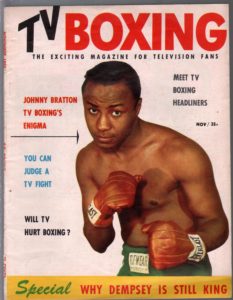

Kid Gavilan’s date with destiny came on a rainy, spring night in 1951, when he climbed in to the ring at New York’s Madison Square Garden to challenge Johnny Bratton for his undisputed world welterweight title. Gavilan was the number-one contender in the welter’s for two years running and was a 2-1 favorite to lift the crown from Bratton. The fight would be Bratton’s first defense of his NBA championship he won sixty-five days earlier against Charlie Fusari in Chicago.

Gavilan pressed the action from the opening bell, scoring almost at will with crisp jabs and lightning combinations. He dominated the early rounds and by end of the fifth; Bratton suffered a deep cut over his right eye, a broken jaw and had a double fracture of his right hand. Even though the fight was still close on the judge’s scorecards, by the seventh it was all Gavilan.

The Hawk continued to impose his will on the broken champion throughout the later rounds and after fifteen; he was declared the Welterweight Champion of the World scoring 11-2 twice and 8-5-1.

Gavilan stood in the center of the ring with the Cuban flag draped on his shoulders. As Latin rhythms pounded from his corner, Kid Gavilan’s hand was raised as the new welterweight champion. Twenty years after Kid Chocolate, Cuba had its second world boxing champion.

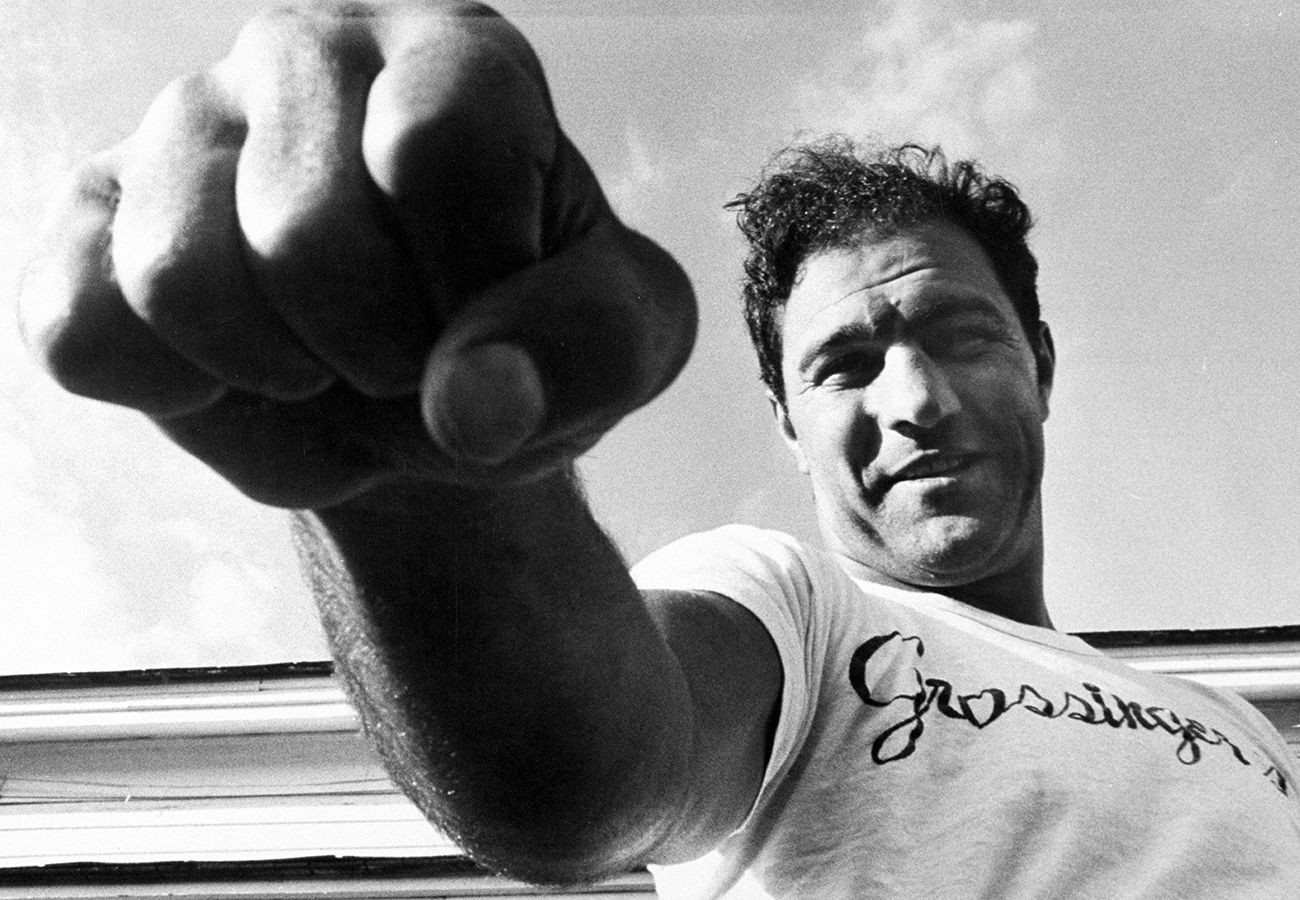

With his flashy style, white shoes and bolo-punch, Gavilan emerged as one of the most popular fighters of the post war, early television era. What he lacked in punching power, he compensated with his tremendous ring savvy, solid boxing strategy and elusive footwork.

Gavilan’s dazzling speed and non-stop offensive arsenal confused many opponents including Michigan State champion Chuck Davey. “When he’d switch to southpaw [left-handed] in the middle of a round, he’d really confused me and threw off my timing,” admitted Davey after their 1953 bout. “And, he’s a lot tougher than I thought.” Davey suffered his first knockout defeat against Gavilan bringing a forty-fight winning streak to an end.

Kid Gavilan was born Gerardo Gonzalez in the town of Berrocal, Camaguey, Cuba on January 6, 1926. At nine years old, Gavilan learned to wield a bolo-knife and went to work cutting sugarcane to help support the family. At twelve he enrolled in the Golden Gloves Boxing Academy to emulate his idol Kid Chocolate. In his first year as an amateur, he won the 75-pound championship and never looked back.

He was introduced to boxing manager, Fernando Balido, who turned Gonzalez over to trainer Manolo Fernandez. Fernandez wanted Gavilan to shave his head and adopt the name of Kid Concito. When Balido balked at the idea, someone suggested he take the name of Balido’s Havana saloon El Gavilan [the hawk] and it stuck. After 60 amateur fights, The Cuban Hawk made his professional debut on June 5, 1943 beating Antonio Diaz by decision after four rounds in Havana.

Gavilan was unique looking at 5’ 10 ½”, 145-155 lbs, with his smooth black skin and round face set with narrowed, almond shaped eyes that reflected his Chinese ancestry. Gavilan was a crowd-pleasing fighter who enjoyed putting on a show for the audience. His arsenal included lightning quick hand-speed, deceptive counterpunching ability and endless stamina.

He introduced fight crowds to his trademark “bolo-punch,” a looping, whirling, half hook, half uppercut that was more show than punch. Gavilan claimed he perfected the punch swinging the bolo-machete on sugar plantations in Cuba. The ‘bolo’ added to Gavilan’s flashy repertoire and made him a media darling to TV fight fans across the country.

After 14 bouts as a professional, Gavilan traveled abroad, fighting for the first time outside of Cuba. He beat Julio Cesar Jimenez by decision after 10 rounds in the first of three consecutive bouts in Mexico. During this tour, he suffered his first defeat, a decision at the hands of Carlos Macalara. In a ten round return match two months later, Gavilan reversed the decision.

The Hawk continued to soar in the rankings and by 1948 had attracted a wide fan base in the United States. He relocated from Cuba to New York City and quickly established himself as a main attraction. In November of that year, he signed to fight the rugged journeyman, Tony Janiro at Madison Square Garden. But one week before the fight, Janiro was injured in training and was replaced by the up-and-comer Tony Pellone.

The Gavilan-Pellone bout turned into a slugfest. While Gavilan concentrated on the body, Pellone did the head-hunting. The fight was even on all scorecards going into the tenth and final round when both fighters met a center ring and banged toe-to-toe for the entire round without either man giving an inch. At the final bell, Gavilan was declared the winner by a decision of 7-3 (twice) and 6-4.

1949 was a breakthrough year for the Keed. He fought a return bout in January against lightweight champion Ike Williams in a non-title match-up. Attempting to revenge an earlier loss the year before, Gavilan pressed the action throughout the fight and came away with the decision. They met for a third time four months later and the outcome was the same.

With the Williams victories on his record, Gavilan and proved himself as the division’s top prospect to steal Sugar Ray Robinson welterweight crown. Robinson was already being referred to as the best pound-for-pound fighter of the era, losing only once in 98 fights to Jake LaMotta, whom he had since beaten three times-while scoring 62 knockouts.

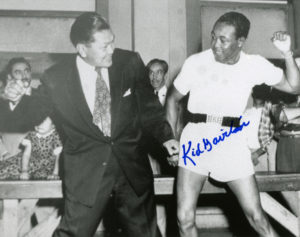

In a 1990 interview for the documentary Latin Legends of Boxing Gavilan remembered meeting Robinson for the first time. “I walked into Robinson’s bar Sugar Ray’s in Harlem,” said Gavilan. “I ordered two shots of whiskey. I said to Robinson, this one is for me and that one’s for you. ‘No!’ Robinson replied, ‘I don’t drink. I’m the world welterweight champion.’ “Not until you’ve beaten me you’re not” said Gavilan. I’m Kid Gavilan from Cuba. Robinson smiled and drank the whiskey. That’s how we met for the first time.”

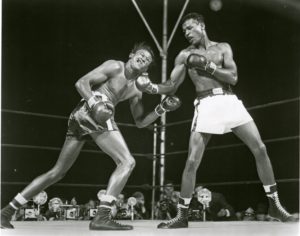

Based on his winning record, Gavilan was matched with the welterweight champ Robinson for the first time in a non-title fight on September 23, 1948 at Yankee Stadium. Though he lost by a unanimous decision after 10 rounds, Gavilan proved to his fans he could dance with the best in the world. Their highly anticipated championship rematch the following year was set for July 11th at Philadelphia’s Municipal Stadium.

Due to the fact there was no live TV coverage or radio broadcast of the fight, 35,000 ticket-holders poured into the stadium on a perfect summer night to see the fight live. Robinson was 12-5 favorite to retain his welterweight title. Insiders knew that Robinson had trouble making the 147-pound weight limit and many believed that in his effort to make weight he make have weakened himself and unable to make it into the later rounds. If so, Gavilan would test him.

Before the start of the fight, Gavilan danced around the ring to the sounds of “The Kid Gavilan Rumba,” played by a Cuban band who had flown in from Havana. Kid Chocolate was at ringside as well as “The Brown Bomber,” Joe Louis who predicted that Robinson would be “skin and bones” if he was able to make the weight limit.

In contrast to the dance party Gavilan’s corner, Robinson looked serious across the ring as he shadow-boxed and posed for photographers. When the gong sounded for the main event, the referee Eddie Joseph called the fighters to ring center for instructions, Gavilan came out from under the Cuban flag he had draped over his shoulders, he faced Robinson eye-to-eye for the first time. Without saying a word, they touched gloves and returned to their respective corners.

The early rounds of the fight were fought cautiously by both fighters. Gavilan moved in and out of Robinson’s range, trying to land the jab and find his rhythm. Sugar Ray concentrated on his hooks to the body following with overhand rights to the head. Gavilan remained elusive, dancing on his toes and jabbing and moving trying to score points and stay out of harms way. At times, he’d even feint grogginess to lure Robinson into a trap, but the seasoned veteran would wait cautiously until The Hawk resumed the action. Robinson kept Gavilan off balance with dazzling footwork and powerful jabs.

The fourth was Gavilan’s best round. A blazing left hook opened a cut over Robinson’s right eye and the Kid targeted it throughout the round. Sugar Ray went into survival mode to minimize the damage. He stayed on his toes till the end of the round to avoid Gavilan’s relentless attack. Between rounds, Robinson’s corner went to work on Sugar Ray’s eye. Robinson’s cut-man applied Monsell solution, a coagulant banned in Pennsylvania because it contained iron, which could cause blindness if used improperly. But, the gamble worked and the flow of blood from Robinson’s eye was brought to a halt.

In the next round, Robinson went on the offensive and began attacking Gavilan from all angles. He danced and fired at the same time, looking for openings and beating Gavilan in every exchange. He was able to tag the hawk

with tremendous body shots and follow- up with the devastating hooks to the head. By the end of the round, the champ was in total control.

Although staggered in the eighth, Robinson was able to ‘stick and run’ until the fifteenth and final round, building a confortable points lead along the way. Towards the end of the last round, Gavilan was staggered with a head shot but refused to go down. Gavilan held his own with Robinson finishing the fight with a non-stop flurry of punches that had the crowd on their feet.

When the bell sounded, Robinson was declared the winner by unanimous decision with scores of 9-6, 9-6 and 12-3. Sugar Ray Robinson retained his crown but Gavilan had shown the world he was a gallant fighter and a true contender for a world title.

The 1950s started on a downbeat for the Kid losing a 10-rounder to Billy Graham at Madison Square Garden. Ringside writers covering the fight thought that Gavilan won the contest, though Gavilan himself admitted he wasn’t as prepared as he should have been. “I was coming off my honeymoon,” said Gavilan in a later interview. “I had less than two weeks of training, but I fought a close fight.”

Six months earlier, Gavilan had been stabbed in the neck in a late night altercation with three men causing cancellation of his previously scheduled rematch with the former lightweight champion Beau Jack. Gavilan’s lackadaisical training regime when it came to non-title bouts caused the hawk numerous setbacks throughout his career. He was inclined to let up in training and lose his usual intensity.

On November 17, 1950, Gavilan had his rematch with Billy Graham, a man he would face four times in his professional career. This time Gavilan was trained and ready for the challenge. Fighting again at Madison Square Garden, Gavilan won a majority decision after 10 rounds. Their next meeting would be for the Welterweight Championship of the World.

The ‘50s were a time of tremendous growth in fight promotions which centered around the man who ruled the roost, Jim Norris. A millionaire, Norris was the Don King of his era. In addition to his controlling interest in Madison Square Garden, he headed the International Boxing Club, which meant he promoted every fight from lightweight to heavyweight. His business associates included reputed New York underworld figures, Frankie Carbo and Blinky Palermo.

In the mid-50’s, the federal government began an investigation on Norris and his associates regarding violation of anti-trust laws, and in 1958, his empire was dissolved by court order. Television then reduced the significance of individual promoters like Norris. Soon television rights surpassed the “live gate” as the promoter’s primary income. The network and their advertisers became boxing’s major players. The emergence of TV sports programs like Gillette Cavalcade of Sports gave unprecedented exposure to hundreds of young fighters.

As one of the most popular star of the early television era, Gavilan headlined the program the record 34 times. Broadcast live on Friday nights from Madison Square Garden, Gavilan brought an excitement to the fight game that hadn’t been seen in years. Along with his handlers Balido, Medina and Lopez, they gave TV audiences what they wanted. Mundito Medina was a trainer who also composed music and loved to sing for the cameras. When their Cuban tempers flared, in-fighting in Gavilan’s corner between rounds was as exciting as what was taking place in the ring.

As they faced off, spewing Spanish adjectives into each others faces as The Kid sat stoically on his stool, seemingly oblivious to the action taking place behind him. Gavilan and company became a popular, sideshow attraction on the weekly TV program.

When Sugar Ray Robinson vacated the welterweight division to campaign as a middleweight, Gavilan was offered another opportunity to become Cuba’s second world boxing champion. On May 18, 1951, at Madison Square Garden, Gavilan faced Johnny Bratton who had won the NBA version of the welterweight crown only sixty-five days earlier by defeating Charley Fusari in a elimination tournament at Chicago.

On fight night, Gavilan was 2-1 favorite to take the title back to Havana. From the opening bell, Gavilan pressed the action, scoring almost at will with crisp jabs and lightning combinations. By the end of the fifth round, Bratton had been cut over the right eye, had suffered a broken jaw and had a double fracture of his right hand. Although the fight was still close on the scorecards going into the seventh, by the gong, it was all but over for Bratton. Gavilan dominated the remaining rounds with Bratton only tossing a few half-hearted punches. Winning the fight with scores 11-2 (twice) and 8-5-2, Gavilan was declared the new Welterweight Champion of the World. With the Rumba playing in his corner, and the Cuban flag draped over his shoulders, Kid Gavilan became only the second world boxing champion from Cuba.

In the first defense of his welterweight title, a rubber-match against Billy Graham, Gavilan won a bitterly fought and controversial decision. In fact, the fight was so close that it prompted some disgruntled observers to dub Graham the “uncrowned champion.” With his split-decision over Graham, Gavilan gained universal recognition as the world champion when the EBU joined the NBA and New York Boxing Commission.

In 1952, the Keed defended his crown against a Miami based Texan named Bobby Dykes. This fight would be the first mixed race boxing contest in the then segregated Florida. The fight was held at Miami Stadium in front of 17,000 fans. After the Hawk scored a knockdown in the second round, the southpaw from San Antonio proved a tough challenge for the champ. The middle rounds went to the long, tall Texan who found his rhythm and was able to score effectively from the outside. The fight was close going into the championship rounds but Gavilan was able to accelerate the action and take a split-decision with scores of 142-141, 145-139, 141-142. Dykes proved he had the style and skill to pose a serious threat to Gavilan’s title.

Later in the year, Gavilan defended his title again, this time against a popular Philadelphia fighter named Gil Turner. Turner, only 21 years old, had an unbeaten record of 31-0. Gavilan-Turner drew 39,045 that paid a welterweight record of $269,667. In the opening round, Turner started with a flurry of punches attempting to put the champion on the defensive, but the crafty Cuban proved too much for the young challenger. By the middle rounds, Turner started to tire and The Kid took over from there. By the eleventh, Gavilan was scoring at will with clean combinations that kept Turner with his back against the ropes. A right-cross and left-hook sent Turner tumbling through the ropes and referee Pete Tomasco stepped in to stop the slaughter with 13 seconds remaining in the thirteenth round.

In October, Gavilan returned home to Havana to meet his old nemesis, Billy Graham. With their last meeting ending in controversy, Gavilan wanted to end the speculation. Gavilan dominated the bout throughout and after fifteen rounds winning a unanimous decision in the first championship bout ever televised outside of the United States.

Gavilan’s made his fifth defense of his welterweight crown on February of ‘53 against Michigan State boxing champion Chuck Davey. Gavilan non-stop style confused the young southpaw who entered the ring with an undefeated record of 37-0-1. Davey had established himself as a popular main attraction and was dubbed “Kid Television,” being featured regularly on Gillette Cavalcade of Sports. But on this night, Gavilan proved he was the best welter in the world.

Gavilan’s style confused the Lansing College graduate. “When he switched to southpaw,” said Davey, “ he completely confused me and threw off my timing. And, he’s a lot harder to hit than I thought.” “I lick all welterweights,” said Gavilan after the fight. “I mush them like spaghetti mush.” By the end of the fight, Davey’s face looked spaghetti mush splashed with marinara sauce. He was dropped from a Gavilan right in the third, cut deeply over right eye and floored three more times in round nine. The challenger remained on his stool after the bell sounded for the start of the tenth, claiming he couldn’t continue after being hit in the throat.

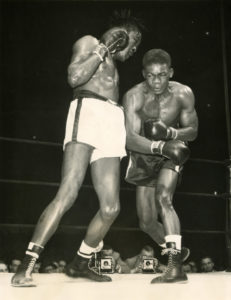

In September of 1953, Gavilan put his title on the line against future ring legend Carman Basilio. The fight took place in Basilio’s home town of Syracuse, New York at the newly constructed Syracuse War Memorial Stadium. Basilio, “the upstate onion farmer,” entered the ring a 4-1 underdog but fought like a champion in his first attempt to win a world boxing title. From the opening bell, Basilio pressed the action and in the second round caught Gavilan on the point of the chin, dropping him for a nine count; the first and only knockdown of Gavilan’s career. Finding his range with his hook, Basilio was able to land it throughout the fight.

As Basilio continued to dominate, the Syracuse fans thought they were witnessing an amazing upset, but The Kid was famous for his second wind. In the seventh, Gavilan began to score repeatedly with perfectly timed jabs and counterpunches from outside of Basilio’s range. With a badly swollen left eye, Basilio rallied in the fifteenth to end the fight strong. The New York Times and The Daily News both thought that Gavilan won by a single round. But, when the split-decision was awarded to Gavilan 8-6-1, 7-6-2 and 5-7-1 the fans got ugly. Both fighters had to be escorted from the ring under police escort.

In November, Gavilan offered a rematch to former champion, Johnny Bratton. In front of his hometown crowd of 19,260 at Chicago Stadium, Bratton attempted to reclaim his welterweight crown. Friday the 13th proved unlucky for the former title holder. From the first round, Gavilan was able to score on Bratton almost at will and by the seventh; it was evident that Bratton didn’t stand a chance. With the heart of a champion though, Bratton went the full fifteen round distance. As Gavilan was announced the winner by unanimous decision, Bratton stood silent in his corner with his right closed and his left badly swollen.

After ruling the welterweight division for 2 ½ years with seven successful title defenses, Gavilan decided to move up in weight and take on the middleweights. In April of ‘57, he squared off against the middleweight champion from Hawaii, Carl “Bobo” Olson. From the opening bell at Chicago Stadium, the fighters attacked each other with bad intentions. Gavilan was the busier of the two, but moving up in weight zapped the little punching power he possessed. Slower but stronger, Olson banged away with both hands to the body and head of his Cuban challenger, trying to keep it close.

In the middle of the tenth, Gavilan and Olsen met in the center of the ring and started banging each other in a flurry, with neither fighter giving an inch. This two minute, toe-to-toe exchange, was later described by New York Times writer, Joseph P. Nichols as “one of the most grueling and furious exchanges in ring history.” After 15 rounds, Olson was announced the winner with scores of 147-141, 147-139 and 144-144. In the end, both fighters were still champions of their respective divisions but the hawk had soared to the heavens for the last time.

Kid Gavilan’s championship reign came to an end on October 2, 1954 at Philadelphia’s Convention Hall. Only six weeks after battling a case of the mumps, Gavilan defended his crown against New Jersey’s Johnny Saxton. The only one with a hometown advantage in the fight was Saxton’s manager, reputed underworld figure, Blinky Palermo. With Palermo in Saxton’s corner, he was guaranteed a victory if he stayed in his feet.

The bout was uneventful and appeared at times a laborious affair with Saxton refusing to lead and Gavilan waiting to counter. The shadowed each other around the ring, round after round, and held each other when they got too close. After 15 uneventful rounds, Saxton was declared the winner by scores of 9-2, 7-6-2 and 8-6-1.

The ringside press, poled after the fight voted 20 out of 22 for Gavilan, but the fix was in. Kid Gavilan would never challenge for another world boxing title. The welterweight roost that The Hawk had sat atop for four years would see six different title-holders over the next three years. Johnny Saxton would be dethroned in his first title defense against Tony DeMarco.

Always popular, Gavilan continued fighting in places like Cuba, England, Argentina, Brazil and France drawing tremendous crowds wherever he went. After four years and twenty-five more contests, Gavilan lost a decision to Yama Bahama in June 1958 and called it quits. He officially announced his retirement on September 11th of that year.

After retiring form the ring, Gavilan moved back to his beloved Cuba. Revered as a national hero, he was given a $200 a year retirement allotment from the Cuban Government. When the Castro revolution confiscated his finca (farm) in 1968, he defected to Miami penniless. He left behind a wife and children and never returned.

Long before Muhammad Ali, Gavilan danced his way into the hearts and minds of boxing fans around the world. He introduced the “Shuffle,” “Shoeshine,” Dancin’ off the Ropes,” “the Stick and Move” and his trademark, “Bolo-punch.” Gavilan was boxings first TV star, and was also the first fighter to ware white shoes, enter the ring with a live band, and carry a flag on his shoulders. Kid Gavilan was a true original.

For a brief time, he was part of Muhammad Ali’s entourage. Kid Gavilan was always proud of the fact he was never knocked out in his entire professional career. In 1966 he was inducted into the original Boxing Hall of Fame and in 1990 he was elected to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastoda, New York. Gerardo Gonzales died of a heart attack in Miami, Florida, February 2003.

The Book Kid Gavilan: The Cuban Hawk by F. Daniel Somrack will be available November 1, 2019 at Amazon Kindle.