One hundred years ago this month, a Michigan farm boy was murdered while eating a leisurely breakfast on a cool morning in Missouri. A small, .22-caliber bullet, killed a larger-than-life figure and changed the world forever. When Stanley Ketchel died October 15, 1910, he was the middleweight boxing champion of the world during the Golden Age of pugilism when title holders were hailed as superstars. Stars who came later, like actor James Dean, another farm boy who died at 24, Stanley Ketchel became America’s first symbol of unrealized potential.

By age twenty-one, this legendary boxer had climbed to the top of the world to become one of the most feared and proficient fighting machines in the history of the prize ring. He became a national folk hero when he jumped two weight classes to challenge the dangerous and unbeatable Jack Johnson for his heavyweight crown. Outweighed by over thirty-five pounds, Ketchel withstood the pressure by white America to defeat the first black heavyweight champion in this David and Goliath mismatch.

Stanley Ketchel’s journey to this historic event was a long and arduous one. It began in Grand Rapids where he was born Stanislaus Kiecal, September 14, 1886 to parents of Polish decent. His father Thomas Kiecal, a native of Russia, was a laborer and his mother Julia Oblinski, a Polish-American home-maker. She gave birth to Stanislaus at fifteen and a second son John the following year.

Growing up on a dairy farm, Ketchel worked with his father and filled his spare time with dime store novels about frontier outlaws like Jessie James, Wild Bill Hickok and Billy the Kid. He discovered early he had a knack for fighting and was expelled from school in the eight grade beating a local bully. After laboring at home for a couple of years, he ran away at fifteen on a westbound train.

Looking for odd jobs or handouts, he wandered across the country, sleeping in mining camps and working for food. Stanislaus passed through Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado and Utah before landing in Butte, Montana as Stanley Ketchel at sixteen. Butte was a booming copper mining town and home to the giant Anaconda Mining Company. Butte was prosperous and a center of night time entertainment with its saloons, theaters, hotels, honky-tonks and fight clubs and the city that offered the opportunities he’d been searching for.

At a fair in Butte, Ketchel saw a boxing booth and decided to try his luck. A ‘barker’ tossed him a pair of gloves and challenged him to last three rounds with the champ for a dollar. The teenager knocked out the star with one punch, took the money and deciding that fighting was the easiest way to make a living. He was immediately offered a job as bouncer and boxing booth fighter at the Casino Theatre taking on all comers for $20 a week. “I hit them so hard they use to fall over the footlights and land in people’s laps,” Ketchel later recalled.

Without formal training and with little more than natural strength, quick reflexes and strong chin, Ketchel turned professional in May 1903. In his first recorded fight he knocked out Kid Tracy in one round then lost a six round contest to a boxing instructor named Maurice Thompson. Undeterred, Ketchel continued in Montana, honing his craft and fought his first 41 matches there, building a impressive record of 36 wins, 2 losses and 3 draws.

Wild Bill Nolan, the owner and operator of the Casino Theater wanted to introduce his rising young star one night as Kid Ketchel or Cyclone Kid Ketchel but Stanley refused. Ketchel admitted later he was surprised when Nolan introduced him before a main event as Stanley Ketchel, “The Michigan Assassin.” The ‘Assassin’ moniker stuck and the newspapers loved it.

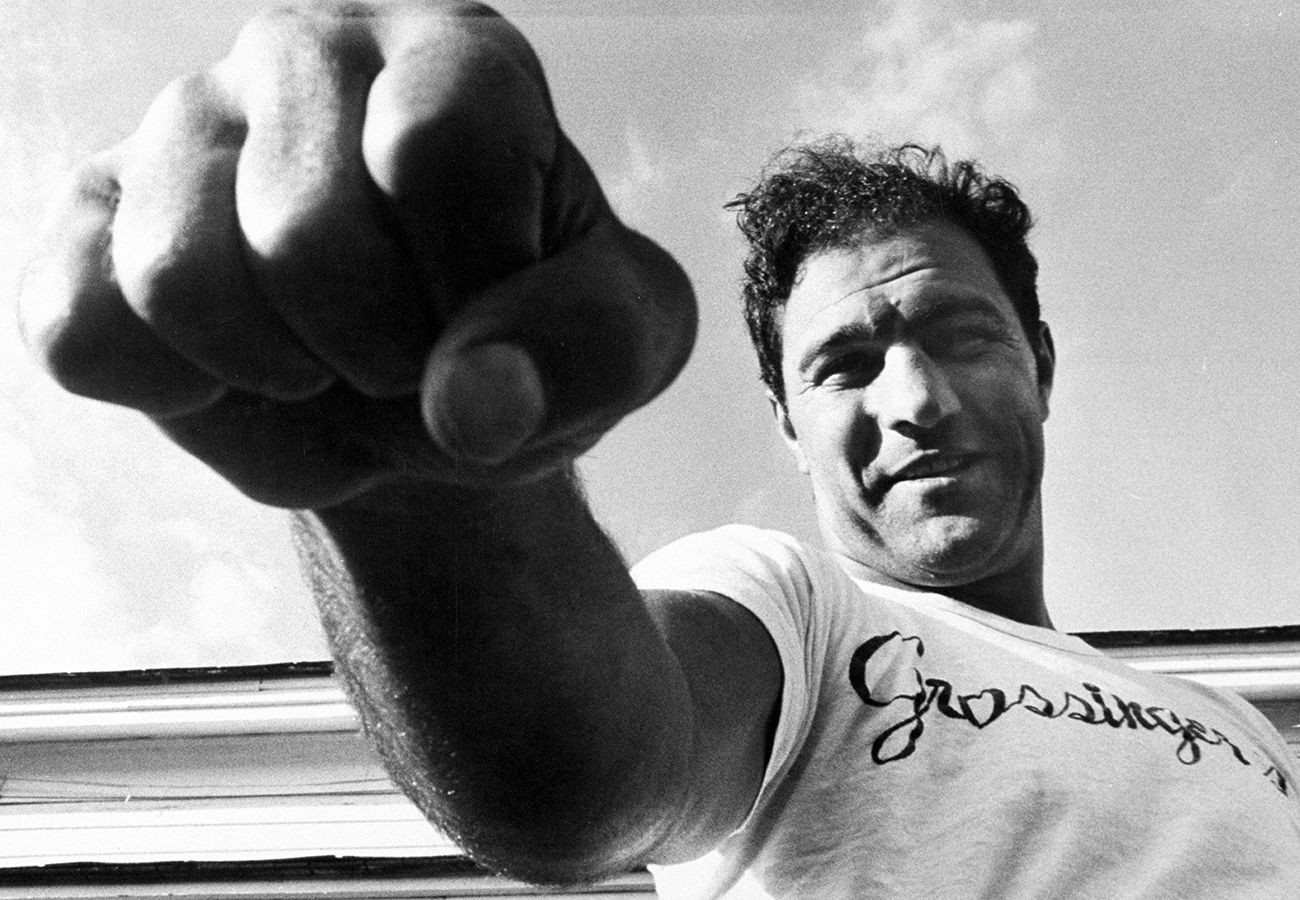

Ketchel’s explosive, non-stop ring style and high knock-out percentage was beginning to attract a large crowds to his bouts and fight promoters were now out bidding each other for his services. Considered handsome with his clean cut profile, blondish hair, and muscular physique, women began reading about him in the daily papers and turning out to his fights in large numbers. Ketchel enjoyed his new found popularity and earned a reputation as a womanizer.

Short on competition in Butte, Ketchel moved his campaign to California in 1907. He won his first three fights there and fought a 20-round draw against Joe Thomas, who touted himself as world‘s champion. In attendance for the Thomas contest was promoter James W. “Sunny Jim” Coffroth who had bet heavily on Thomas. Impressed with Ketchel’s commanding performance, Coffroth invited the fighter to stage a rematch at his newly built Mission Street Arena near San Francisco. Ketchel won the scheduled 45-rounder by knockout in the 32nd and claimed the world middleweight championship for himself.

On February of 1908, Ketchel faced off against Mike “Twin” Sullivan, an east coast fighter who also claimed to be champion. Ketchel knocked him out in the first round and gained general recognition as the undisputed middleweight king. Today boxing historian’s agree that Sullivan was the lineal middleweight champion at the time.

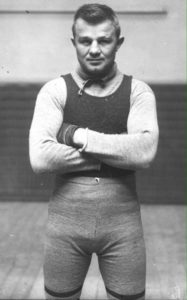

Ketchel first title defense was a knock-out in 20 rounds against Sullivan’s brother, Jack “Twin” Sullivan, also a former champion and then beat Billy Papke, the Illinois Thunderbolt by decision in 10. He topped Hugo Kelly by a knockout in three, than beat Joe Thomas for a third time. Then in September 1908, he lost his championship belt to Papke by a knockout, but the bout was marred in controversy.

Before the opening bell, it was customary for fighters to touch gloves. As referee James J. Jeffries finished his preflight instructions, Ketchel extended his hand for a shake and Papke smashed him in the face with an explosive, blinding punch that drove him into the ropes. As Papke pressed the action, the dazed and confused Ketchel was unable to defend himself. He was knocked down four times in the first round and his right eye was closed at the start of the second. He fought round after round with determination and heart but it wasn’t enough. The fight was stopped in the 12th and Billy Papke was declared the new middleweight champion.

The Sept. 8, 1908 San Francisco Chronicle reported the event, “When James J. Jeffries, the referee, called time and Ketchel walked to the center extending his hand for the shake, Papke ignored his hand and sailed into the Michigan killer with the fiery tempestuous spirit that entitled him to be called the “Illinois Thunderbolt.”

Ketchel was enraged by the cheap shot and immediately petitioned for a rematch. This time Ketchel was in complete control. At the first bell, he met Papke in the center of the ring with a barrage of punches from every angle and never let up. Ringside reporter W. O. McGeehan wrote, “Hatred inspires every blow in the fight. Papke’s stubborn courage is of no avail before the power of the Assassin.” A pulverizing body blow crumpled Papke in the first round and from then on, it was all Ketchel.

Ketchel told his rival, “It took you 12 rounds to stop a blind man. I’m going to let your eyes stay open until the 11th so you can see me knock you out.” In the 11th, an explosive left sent Papke crashing to the canvas. “It was a punch that shook his entire frame and sent his head crashing against the wooden platform,” wrote McGeehan. “Pain racked and with his heart beaten out of him by body punches in the first few rounds…it was all over in that punch.” Stanley Ketchel became the first boxer in history to win the middleweight championship twice.

Nat Fleischer, boxing historian emeritus and founder of the Ring Magazine wrote, Ketchel was one of the greatest fighters of my time. All stone and ice concentration when he entered the ring. The moment he entered the ring, his eyes were the eyes of a killer. Ketchel scorned the word retreat. A demon of the roped square, he made his opponents think that all the furies in Hades had been turned loose on them. He got his punches away from all angles. If he missed with one hand, he would nail him with the other. He was game as a bulldog and tough as a bronco.”

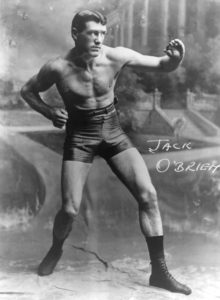

Ketchel began 1909 defending his title in a 10-round no-decision affair against reigning light heavyweight champion “Philadelphia Jack” O‘Brien. In the rematch a few months later, Ketchel knocked O’Brien out cold in three rounds. He beat Papke by decision in their fourth and final brawl that went the full, 20 round distance and left both fighters with broken hands. Next he set his sights on the crown jewel of sports, the heavyweight championship of the world.

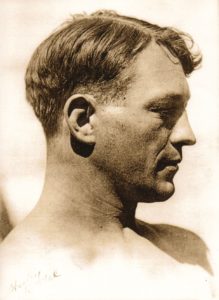

Jack Johnson had been the number one contender for the heavyweight championship for several years and because of his race, he was forced to chase champion Tommy Burns around the world for a shot at the title. In December 1908, an Australian promoter, Hugh D. (Huge Deal) Mcintosh offered Burns the sum of $60,000 to fight Johnson in Sydney. Outclassed by Johnson, the mismatch went on for fourteen rounds before the police intervened and stopped the massacre to save Burns the embarrassment of a knocked out. Johnson became the first African-American world heavyweight boxing champion.

Once Johnson had the title in his possession, he flaunted his superiority and remained cocky and bitter. He was instantly despised by white America for refusing to abide by the ‘unofficial’ rules of conduct imposed on Negro’s at the time. In an age where a black man could be lynched for even flirting a white woman, Johnson courted white women openly and married two of them.

White America was desperate to find a successor for their black menace. This period in boxing became known as the “great white hope” era. The search for a white contender who could return the crown to the white race officially began when Jack London, working the Johnson-Burns fight as a special correspondent for the New York Herald, issued his famous proclamation: Jeffries (James Jeffries, the retired, undefeated heavyweight champion) must emerge from his alfalfa farm and remove the golden smile from Johnson’s face. “Jeff, it’s up to you . . .”

— New York Herald, December 27, 1908 [America’s search for a Great White Hope ended on April 5, 1915, when Jess Willard’s defeated Johnson in Havana, Cuba].

Johnson enjoyed his title, defending his crown several times against lesser opponents. All challengers were easily defeated by his far superior ring skills. The only fighter on the horizon who could test Johnson was two weight classes below the heavyweight limit. By now Stanley Ketchel had beaten all competition in his division and was considered a legitimate challenger for Johnson’s throne.

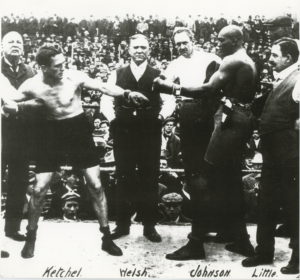

Coffroth offered Johnson $65,000 to defend his title. With Johnson weighing in at 205 ½ against Ketchel’s 170 ¼ the ‘Galveston Giant’ felt confident in the outcome. A preflight agreement was reached between both camps to “carry” the fight for the full 20-rounds so motion-picture cameras could record the action. The fight film would later have a worldwide theatrical release and the fighters would split the box-office profits.

The film shows the muscular heavyweight man-handling Ketchel around the ring, knocking him down in the 2nd and 3rd rounds. By the 11th, Ketchel, bruised and bleeding from Johnson’s rough tactics feels their preflight agreement was violated. In round 12, we see give-and-take exchanges when suddenly Ketchel explodes with a right hand and Johnson crashes to the canvas. Ketchel steps back as Johnson rolls around for a few seconds before pulling himself back up.

Sensing a double-cross, Johnson retaliates with a devastating right uppercut punch that topples Ketchel like a fallen tree. The power of the blow carried so much force, it ripped several of Ketchel’s teeth off at the root. (found later embedded in Johnson’s right glove). The Johnson-Ketchel bout was called the Fight of the Century and it made Stanley Ketchel an international icon. A rematch between the champions was assured.

In the months that followed, Ketchel moved camp to New York and engaged in several non-title bouts. He fought a draw with Frank Klaus and went six rounds with Hall of Fame boxer, Sam Langford. He then recorded knock outs against Porky Dan Flynn, Willie Lewis and Jim Smith. In his last fight at New York’s Sporting Club he soundly defeated Smith. At reporter at ringside covering the fight wrote, “Ketchel rushed and hammered Smith all over the ring, cuffing him with lefts and rights. Ketchel used little defense, relying on the sledge-hammer blows that he could deal out with either fist. An overhand right flashed through Smith’s defense and finished him. Laughing with joy over his win, Ketchel waved to the roaring crowd, hopped over the ropes, and left the ring, never to return.

Ketchel knew all the beer parlors and honky-tonks in New York City and his popularity made him a target to all the fast living women who frequented them. He had a brief, passionate affair with the famous model and chorus girl, Evelyn Nesbit. The Gibson Girl made headlines around the world during the murder trail of her ex-lover, architect Stanford White, by Nesbit’s jealous husband Henry Kenndall Thaw. Hollywood would immortalize her in the 1955 film, “The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing.”

Another court case involving Ketchel was reported by the Portland newspaper: Stanley Ketchel has settled a $10,000 breach of promise suit out of court. Miss Elizabeth Houman, a Grand Rapids, Mich., sued him for triffling with her affections.

“The girl’s charms intoxicated me,” explained Ketchel. ” I just couldn’t withstand those goo-goo eyes, those rosy lips and that dainty willowy figure.

In a careless moment I asked her to marry me, and now that I have come to my senses I have changed my mind.”

-Portand Daily Advertiser, June 28, 1909

Cashing in on celebrity, Ketchel was now earning $1,000 a week for Vaudeville appearances and exhibitions. He owned a bright red Lozier racer, one of the fastest and most expensive automobiles of the day. He had enough money to last a lifetime but the years of fast living and faster women were beginning to take their toll. Back in Grand Rapids for a rest on Little Pine Island Lake, Ketchel had a chance meeting with an old family friend, Michigan native, Rollin P. Dickerson. R.P “Pete” Dickerson was successful Missouri banker, business man, rancher and sports buff.

Dickerson had been a private in the Spanish-American war, but in Springfield he was known as “Colonel.” He owned an 860-acre ranch in the Ozark Mountains. He invited Ketchel down to the ranch to get his health back and take in some fresh air training. On September 15, 1910, Ketchel and his trusty Colt .45 pistol arrived at Dickerson’s Two Bar Ranch. He carried the Colt everywhere and slept with it when he was alone. Stanley was welcomed by the ranch hands and introduced to Goldie Smith, Dickerson’s attractive housekeeper and cook and her common-law husband, Walter Dipley.

On the morning of October 15, Ketchel was flirting with Goldie in the kitchen as she prepared his breakfast. Seated with this back to the door and his Colt .45 safely tucked in his belt, Ketchel was startled when Walter Dipley burst through the door brandishing a .22 caliper rifle yelling, “get your hands up.“ As Ketchel slowly reached for his Colt, Dipley shot him in the back. Ketchel fell to the floor mortally wounded. Dipley and Smith took a wad of money from Ketchel’s pocket and fled.

As Ketchel lay dying, he told the ranch Forman that Smith and Dipley had robbed him. Dipley fled from the scene but Smith was soon apprehended by the police. She told the authorities that Ketchel had raped her and Dipley was simply defending her honor. Goldie’s story soon fell apart and she admitted complicity in the shooting but claimed she didn’t know Dipley planned to shoot the fighter. Dickerson immediately offered a $5,000 reward for Dipley, Dead or Alive. He was captured the following day on a neighboring farm.

Col. Dickerson chartered a special train to transport the wounded champion to a hospital in Springfield. Two physicians were on the special to accompany Ketchel while a third worked to locate the slug that had entered the boxer below his right shoulder and lodged in his lung. At approximately 7 O’clock that evening, Ketchel whispered, “I’m so tired, take me home to mother,“ and died. He was 24 years old.

A century has passed and Stanley Ketchel is still remembered was one the greatest boxers of all-time. His individualism and raw courage helped defined America and prove that a man could be whomever and whatever he wanted to be. At the time of his death, he had his sights set on a rematch with Jack Johnson. He may have become the first and only middleweight to win the world heavyweight championship. We’ll never know.

The legendary champion was returned to Michigan where his funeral took place October 20, 1910. The procession to his final resting place at Holy Cross Cemetery in Grand Rapids, drew a crowd estimated in the thousands. Two years after the funeral, Dickerson paid $5,000 for the 10-foot high, solid Vermont marble monument placed over Ketchel’s grave. Inscribed on the Monument are the words:

Stanley Ketchel

Born Sept. 14, 1886 – Died October 15, 1910

A Good Son and Faithful Frien

Both Walter Dipley and Goldie Smith were found guilty of first-degree murder at a jury trial in January 1911 and were sentenced to life in prison. Goldie Smith had her murder conviction overturned on appeal and only served 17 months for robbery. Walter Dipley stayed in prison for 23 years before he was paroled. He died in 1956.

The Legend Lives On…

Stanley Ketchel’s Professional Ring Record: 52 wins, 4 losses, 4 draws and 4 No-decisions, with 49 wins by knockout.

Stanley Ketchel was inducted into the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame in 1959.

In 1990, the legendary Stanley Ketchel was part of the inaugural class of inductees into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Ring Magazine founder Nat Fleicher rated Stanley Ketchel as the greatest middleweight champion of all time.

A 1996 Ring magazine reader’s poll ranked Ketchel the # 4 all-time middleweight in their All-Time Divisional Ratings and among the 20 greatest fighters of the 20th century in 2000.

Boxing Writer/Sports Historian Bert Randolph Sugar ranks Stanley Ketchel the eighth-best professional boxer of all time.

The 1909 Jack Johnson – Stanley Ketchel fight was ranked #24 all-time greatest fight in history.

A 2003 Ring Magazine poll voted Ketchel #6 among the 100 greatest punchers of all time.

The IBRO (International Boxing Research Organization) rated Ketchel the #3 all time middleweight in their 2005 member poll.

Biography: “The Michigan Assassin” – The Saga of Stanley Ketchel by Nat Fleischer, RING Editor 1946

Biography “Stanley Ketchel: A Life of Triumph and Prophecy” by Manuel A. Mora. 2007

Subject of the Book: The Killings of Stanley Ketchel” by James Carlos Blake. 2006

Subject of the Short Story: “The Light of the World” by Ernest Hemingway.

Jack Johnson vs. Stanley Ketchel October 16, 1909