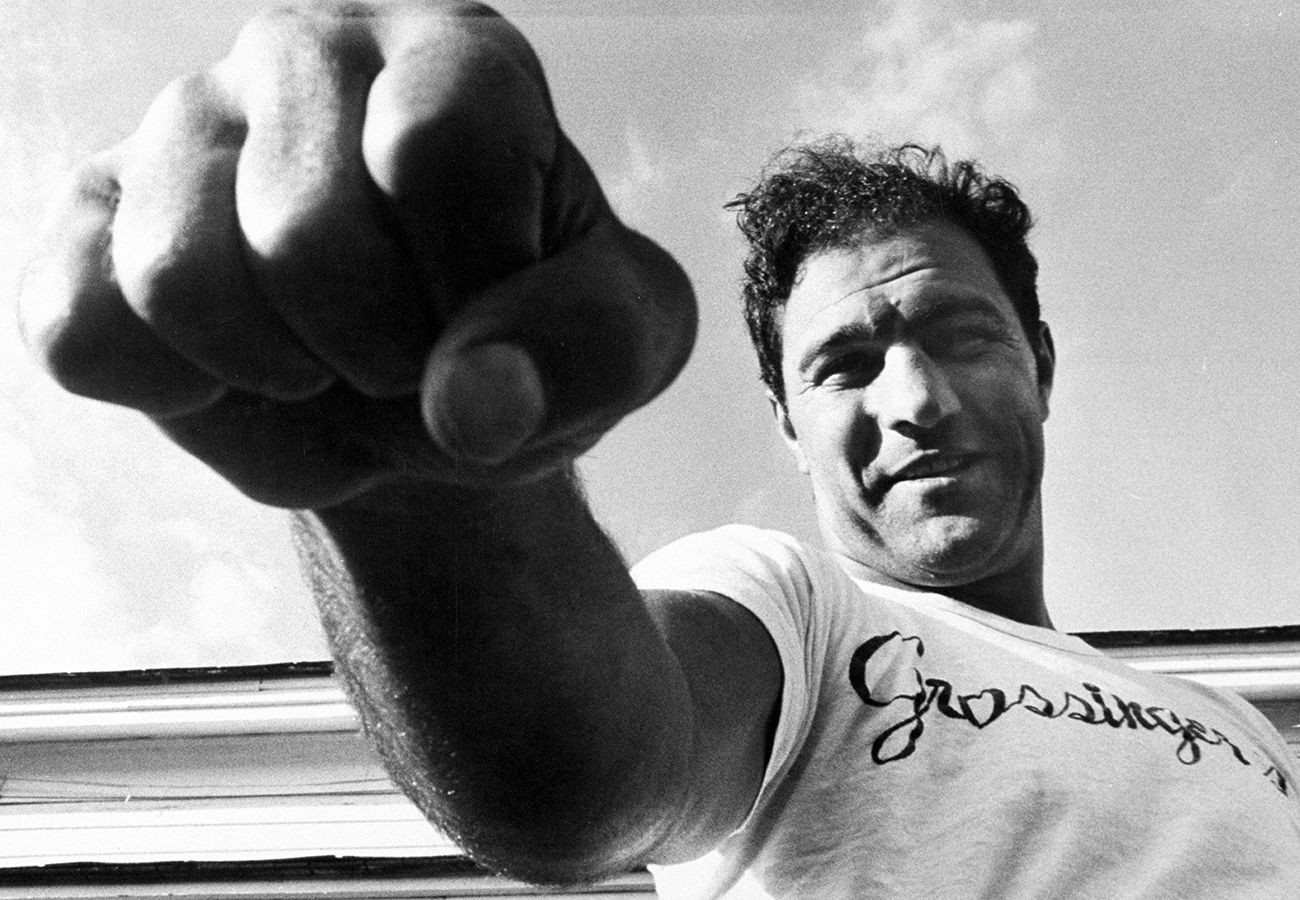

Benny Leonard “The Ghetto Wizard”

The Roaring Twenties, an era of sports legends like Babe Ruth, Ty Cobb, Johnny Weissmuller, Bill Tilden and Jack Dempsey coincided with the generation of outstanding Jewish athletes who dominated the sport of boxing. Benny Leonard, “The Ghetto Wizard,” was the Golden Boy in the golden age of great Jewish fighters.

Born Benjamin Lanier in 1896, Leonard was raised by Orthodox Jewish parents in the Jewish ghetto on New York’s lower east side. After spending his boyhood fighting local Irish and Italian challengers on the streets of the city, he turned professional at 15 to earn some money for his family. His named changed to Leonard when ring announcer Peter Prunty introduced him as Benny Leonard and the record keeper recorded it.

After losing his boxing debut by knockout, Leonard made some adjustments in his style and adopted a scientific approach to training. His quick analytical mind allowed him to recognize weaknesses in opponent’s styles and capitalize on them. A student of the game, he used each bout as a stepping-stone to greater learning. Although he was KO’d in three of his first 13 bouts during his development phase, he wouldn’t be KO’d again until his last fight, some 20 years and 200 bouts later.

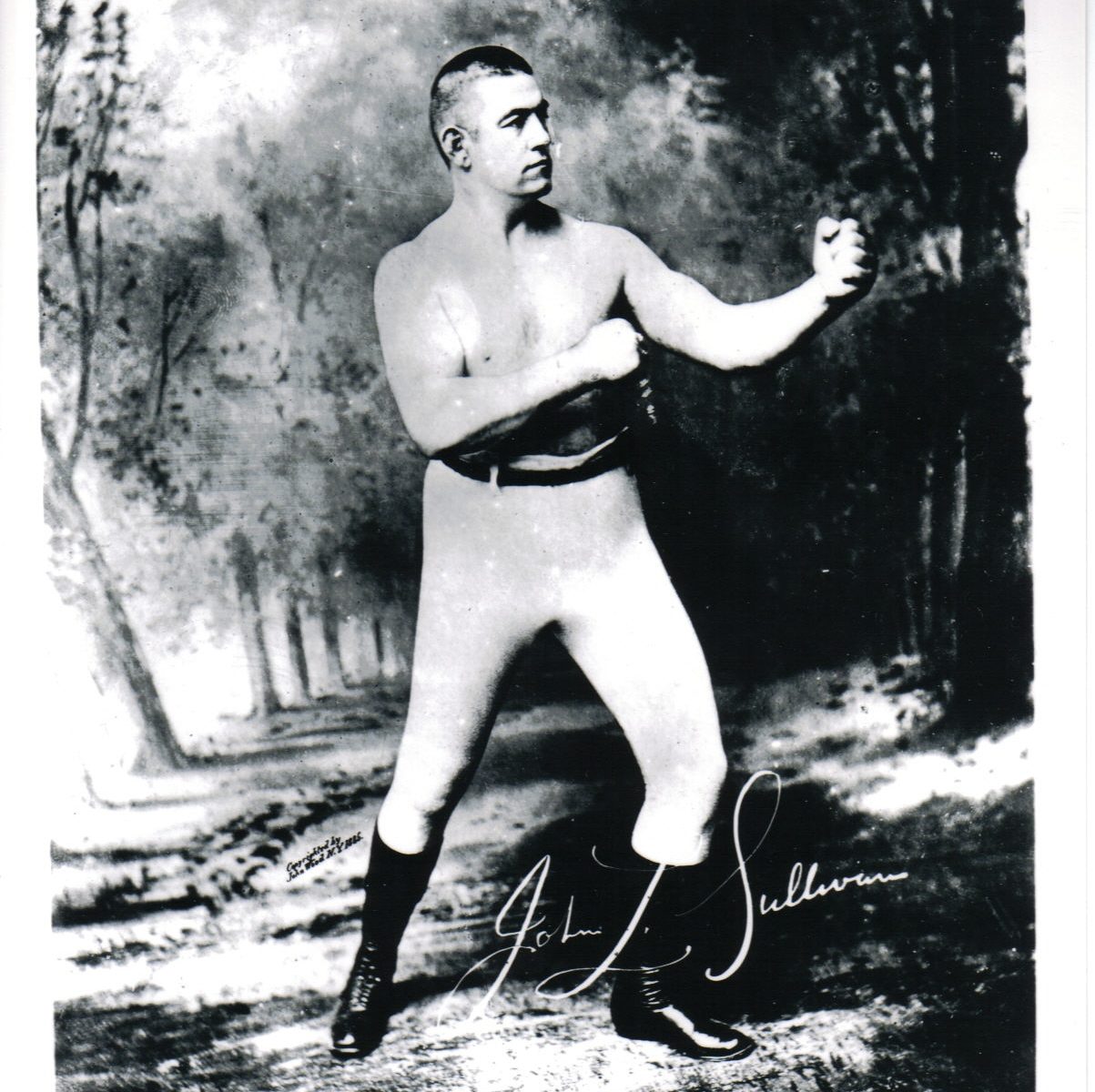

Like his predecessor and idol, lightweight champion Joe Gans, Leonard slowly transformed himself into a boxing master. Though Leonard’s intellect separated him from most of his peers, his physical abilities were second to none. Sportswriter Hayward Broun wrote in 1922, “Leonard’s left handed jab could stand without revision in any textbook. The way he feints, ducks, sidesteps and hooks is impeachable.“

On his march to the title, Leonard took on many past or future champions like Johnny Kilbane (Featherweight), Johnny Dundee ( Featherweight, Jr. Lightweight), Freddie Welsh (Lightweight) and Rocky Kansas (Lightweight). Leonard’s first shot at the title came against Freddie Welsh March 31, 1916 in a no-decision contest in which Benny could only win by knockout. The bout went the distance but the newspaper writers voted unanimously for Leonard.

Leonard engaged in twenty-five more bouts with two no-decision losses to Johnny Dundee and Freddie Welsh before getting another try at Welsh’s lightweight title. Under the shrewd boxing management of Billy Gibson, Benny now demanded bigger paydays and another title try. He faced off with Welsh May 28, 1917 at the Manhattan Casino for the Lightweight Championship of the World.

Now in his prime, Leonard was in complete control of the action and dominated Welsh throughout the fight. Welsh was down three times in the 9th before referee Kid McPartland finally stopped the slaughter with Welsh was dangling defenselessly on the ring ropes. New York’s Jewish community finally had their champion. Hayward Broun called Benny Leonard, “the white hope if the orthodox.”

Over the next several years, Leonard continued his winning streak and along the way, knocked out Leo Johnson in a 1918 title bout. A year later, Leonard fought the great Ted “Kid” Lewis in a no-decision contest with Lewis’ title on the line. The fight ended in a Draw with Lewis getting the newspaper decision. Benny also dropped a four round newspaper decision to former lightweight champion Willie Ritchie later that year.

Leonard risked his title several times the following year against the best of his star-studded division. Young Erne, Johnny Dundee, Joe Welling, Ritchie Mitchell, Rocky Kansas all took a crack at his title. On July 5, 1920 Benny was almost dethroned by Chicago’s master left hooker, Charley White. In their rough and tumble battle, Leonard was knocked out the ring in round five and rebounded to have White down five times in the ninth. Benny finally won the bout by KO in the 9th.

In his rematch with Willie Ritchie, Benny was dropped in the first round and came within two seconds of losing his crown. His ability to recover quickly allowed him to come out in the next few rounds and keep Ritchie on the defensive. Once in control, he knocked Richie to the canvas three times before the fight was stopped in the 6th.

In June 1922, in front of 18,000 fans at the New York Velodrome, Leonard challenged Jack Britton for his world welterweight title. According to ringside observers, Leonard was out shined by Britton and losing the bout on points when, in the 13th round, Benny threw an accidental low blow and Britton dropped to his knee crying foul.

As referee Patsy Haley was tending to Britton in the center of the ring, Leonard ran around Haley and banged Britton on the jaw with a hard right and Britton falls back on the canvas. Haley immediately disqualifies Leonard for the foul and Britton retains his title. Leonard’s motivation for ending the bout on a foul has remained a mystery. It’s one of the most disputed and controversial endings in the history of boxing.

The following month, Leonard put his title on the line against his toughest opponent among the lightweights, Philadelphia‘s “Lefty” Lew Tendler. The dramatic confrontation took place at Boyle’s Thirty Acres, New Jersey in front of 50,000 spectators. It was the largest money producer in the history of the lightweight division. Gross receipts were $327, 565 which gave Benny a purse of $101,755 and Tendler $62,000. Fight promoter “Tex” Richard grossed over $90,000 on the event.

Tendler dominated the early rounds and staggered Leonard in the first round. By the third Benny was bleeding from the nose. In the 8th, Leonard caught a left on the chin and dropped to one knee. He barely beat the count and distracted Tendler by talking to him and survived the round. Leonard won the 12 round No-decision fight but said later “ Lew gave him the worst licking I ever had in my life the first time we fought.”

In his second meeting with Tendler at Yankee Stadium in July of ‘23, it was a winner take all affair. With the experience he gained in their first fight, Benny was able make adjustments and control Tendler for 15 rounds and win a unanimous decision. Leonard – Tendler II was another financial success for “Tex“ Rickard with gross receipts over $450,000.

Following the second Tendler bout, Benny had two more non-title bouts and then to comply with his mother’s wishes, he hung up his gloves. Benny Leonard officially announced his retirement January 15, 1925. He had amassed a fortune during his ring career and had enough money invested in stocks and bonds to take care of his family. The Wall Street Crash October 1929 changed all that. It’s estimated Leonard lost several million dollars invested in the market.

In 1931, after a six year retirement, Benny was forced to return to the ring as a welterweight. Paunchy, slower, his wizardry gone, Leonard was still able to string together 19 straight victories against lesser talent before facing off against top welterweight contender Jimmy “Babyface” McLarnin. One of toughest welterweights of all time, McLarnin outshone Leonard in every possible respect. Benny was knocked down in the second round and the bout was finally stopped by referee Arthur Donavon when Leonard appeared defenseless in the 6th.

Benny Leonard retired for good in October 1932 with a professional ring record of Bouts 219, Wins 183 (70 KO), Losses 24, Draws 8, No-Contests 4. In retirement, Benny became a top fight referee. He died of a heart attack reffing a bout at St. Nicholas Arena April 18, 1947. He was 51 years old.

Boxing historian Herb Goldman ranked Leonard as the # 1 Lightweight of all time. Writer Charley Ross ranked him as the #1 lightweight of all-time. Ring Magazine founder Nat Fleisher ranked Leonard as the #2 all-time lightweight. Fistiana ranks Benny Leonard the #2 all-time lightweight.

Hall of Fame Inductions:

Ring Boxing Hall of Fame: 1955

International Boxing Hall of Fame: 1990

World Boxing Hall of Fame: 1980

National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame: 1996

International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame: 1979